My relationship with Cordwainer Smith’s work began in high school thanks to my 11th grade AP English teacher, Mr. Hom. I grew up in an abusive family and I hated going home, so I used to stay after school as long as I could, talking with my teacher about the weird worlds of literature.

He introduced me to many of my favorite literary works, from the musings on philosophy of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance to the maniacal defiance of godhood in Moby-Dick, as well as the suppressive thought police of 1984. But the writer that stands out most was one I’d never heard of before: Cordwainer Smith.

Mr. Hom would tell me all sorts of fantastic stories about the Instrumentality, how Smith was influenced by his time growing up China (his godfather was Sun Yat-Sen, the founding father of the Republic of China), and the unique way he incorporated Asian myth and culture in a way that had rarely been done before. The idea of there existing science fiction incorporating Asian elements was so appealing to me, especially because there weren’t any writers of Asian descent I knew who wrote science fiction back then. What was odd was that I’d never heard of Smith and couldn’t find his books at the local Borders (back when it still existed) or Barnes and Noble. I wasn’t familiar with Amazon yet either. Because I had such a hard time finding his books, a part of me even wondered if my teacher had written the stories himself and was using Cordwainer Smith as an avatar for his own ideas.

But that’s when used bookstores came to the rescue. There were four local bookstores I loved visiting, musty old places that were filled with stacks of used science fiction paperbacks. It felt like I’d entered into an ancient hub with these books, their weird and almost grindhouse style covers bright with gaudy hues, their spines in a frail state that would break apart if you weren’t careful. I quickly learned these strange books were portals to fantastic worlds at $2-$5 apiece, a treasure trove of strange and bizarre realities. The booksellers always had great recommendations and when I asked about Cordwainer Smith, I remember the excitement and surprise I was met with as they considered Smith special, although somewhat obscure for general readers.

Even with access to the used bookstores, his stories were hard to track down and it was an ecstatic moment when I finally found his collection, The Best of Cordwainer Smith. I immediately jumped into the first story without waiting to go home, reading, “Scanners Live In Vain” at the bookstore.

The strangeness of the story struck me, where the titular Scanners cut off all sensory input to the brain except for their eyes and live in a cruel, dehumanized existence in order to survive the “Great Pain of Space” in interstellar travel. “The brain is cut from the heart, the lungs. The brain is cut from the ears, the nose. The brain is cut from the mouth, the belly. The brain is cut from desire, and pain. The brain is cut from the world,” Smith explained.

It was a humanity completely split apart from itself, a forced isolation in the future where even the assemblage of a human was carved into separate divisions to serve others. The symbolic slavehood was the ultimate act of numbing, manipulating science just so the Scanners could endure. It was something I could relate to as I’d emotionally split myself apart in order to better deal with some of the more difficult aspects of my life.

Even more disturbing was the fact that when a new technology is discovered that would make their seemingly terrible function obsolete, the Scanners react defensively and try to eliminate the invention. Protecting the status quo and maintaining authority takes precedence for them, even if it would greatly improve and benefit their lives. They ultimately vote against their own self-interests in a misguided attempt at preserving their terrible plight.

High school often felt like it was a cluster of different sects and cliques maintaining their hold over their various domains while we were enslaved to a codified system that categorized us within the school walls. Like the Scanners, the cliques had their own rituals and quaint beliefs, and would do anything to protect them. In the short story, one of the Scanners who remains “cranched” by having his senses reconnected is the only one to realize that this new invention needs to be implemented, causing him to defy the other Scanners. Smith’s characters are often about outsiders looking in with different perspectives.

I related to that view and kept reading when I took the collection home. Stories like “The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal,” “The Game of Rat and Dragon,” and “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard,” all had intriguing titles with equally fascinating premises behind them. Each of them was connected by the “Instrumentality,” a different type of government that believed in the harmonization of power while overseeing groups like the Scanners. It wasn’t a structure that imposed their will on people, but rather a council of individuals who help move humanity as a whole forward.

I was thrilled to share my discoveries with my teacher, Mr. Hom. I’d find a few more collections of Smith’s work and devour them. I was especially surprised to learn that one of my favorite Chinese novels growing up, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, influenced the structure and style of some of the stories. My teacher and I used to spend hours after school analysing and dissecting what made Smith’s works so powerful. I was short on role models and as I mentioned, I dreaded going home. My long talks with Mr. Hom were a chance for me to imagine different worlds and try to make sense of the random violence that awaited me. I’d always loved writing, but it was under his guidance that I really began finding my voice and channeling characters that defy terrible circumstances through imagination and a desire to endure.

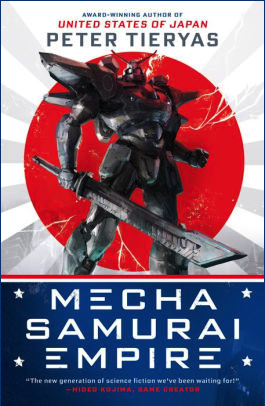

Buy the Book

Mecha Samurai Empire

Many years later, when it came time to writing my own science fiction book about students aspiring to be mecha cadets (the new standalone book in the United States of Japan universe, Mecha Samurai Empire), I thought back on my high school years. I wasn’t a straight-A student and while I loved English and history, there were lots of subjects I struggled with (it didn’t help that I spent a lot of my time reading newly discovered science fiction and fantasy books in class by hiding them behind my textbooks). But still, I dreamed of being a writer.

In that same way, the main protagonist, Mac, struggles just to keep afloat at school. He doesn’t have a rich family, doesn’t have any realistic hopes of making something of his life; instead, he takes solace in mecha-related games (just as I did in books and videogames back then). As corporal punishment is part of school life, Mac and his friends do their best to avoid beatings at school. But he keeps persisting because of his dream of becoming a mecha pilot. He represents an intentional defiance of the trope of a prodigious and gifted orphan finding success through their rare talent, even against intense opposition. All the main characters struggle through with grit, persistence, and a whole lot of suffering. They’re fighting the odds to drive mechas, even if they’re not the most gifted pilots around.

It was important to me to incorporate the same sense of wonder and excitement that I had discovering the worlds of Cordwainer Smith into the high school students of Mecha Samurai Empire as they learn more about mecha piloting. There are direct tributes to Smith, like experimental programs try to get mecha pilots to neurally interface directly with their cats (an idea explored in “The Game of Rat and Dragon”) and the fact that one of the mecha scientists is named Dr. Shimitsu (for Smith). I also thought of the elaborate rituals the Scanners had when devising the lore and culture of the mecha pilots. There are references to events that are never explained in Smith’s stories, wars that are never elaborated upon but that hint at so much and provide fodder for the curious. There’s one scene in Mecha Samurai Empire where the cadets get together in an initiation ceremony far below the depths of Berkeley Academy. One of the senior cadets discusses their past which is a tribute to the lessons I learned from Smith’s worldbuilding:

“Welcome to the Shrine of the Twelve Disciples. We are deep underneath Berkeley in this sacred shrine where only members of the mecha corps and the priests have access. The first twelve mechas and their pilots were called the Twelve Disciples for their devotion to the ideals and principles of the Emperor. They risked everything for the preservation of the United States of Japan. The Disciples were six women and six men, representing multiple ethnicities, united under the banner of the rising sun… Many questioned the Disciples, particularly the other branches, who were jealous. But after the Twelve Disciples fought back the horde of Nazis who wanted America for themselves and died in those battles to save the USJ, all opposition faded. Posthumously, the Emperor granted each of the Disciples a position in the great Shinto pantheon.”

Carved into the walls are Japanese letters describing the exploits of the Disciples, their backgrounds, what they achieved in battle. Each of their pilot suits is in an airtight glass display case. Painted on the ground is the emblem of an armored fox, snarling defiantly, ready to pounce on its prey. There is also a whole gallery devoted to their feats painted by the famous Hokkaido artist, Igarashi from his G-Sol Studios. His artistry is phenomenal, and I gawk at the treasure trove of our legacy.

Looking back all these years later, science fiction for me wasn’t just an escape from reality. It was a way for me to cope and find a different, more nuanced meaning in what seemed like the random cruelty of the world. I was similar to one of the Scanners, cutting off different parts of myself emotionally from each other so I wouldn’t feel the pain all at once. The new tech that brought relief and change was writing.

Making me feel especially happy is that kids growing up now have so many wonderful and inspiring Asian writers and voices in the SF and fantasy space to read, from Ken Liu to Zen Cho, Aliette de Bodard, Wes Chu, JY Yang, R.F. Kuang, and more. Even if scanners live in vain, at least they won’t have to feel alone.

I don’t remember many of the things I studied in high school, what I learned in all those sleepless nights preparing for AP exams, and sadly enough, even the majority of my friends back then. But I do remember reading Cordwainer Smith for the first time and being awestruck at his storytelling as I talked with my teacher about what made his work so great. After the painful partitions I’d set up for myself, it was part of what would eventually help make me whole again.

Peter Tieryas is the author of Mecha Samurai Empire and United States of Japan, which won Japan’s top SF award, the Seiun. He’s written for Kotaku, S-F Magazine, Tor.com, and ZYZZYVA. He’s also been a technical writer for LucasArts, a VFX artist at Sony, and currently works in feature animation. He tweets @TieryasXu.

Peter Tieryas is the author of Mecha Samurai Empire and United States of Japan, which won Japan’s top SF award, the Seiun. He’s written for Kotaku, S-F Magazine, Tor.com, and ZYZZYVA. He’s also been a technical writer for LucasArts, a VFX artist at Sony, and currently works in feature animation. He tweets @TieryasXu.